The ability to learn language always amazes me. Given a supportive environment most young children will learn the language of the home effortlessly; forming their own hypotheses about its use and very quickly understanding the complexities of language structures and nuances of meaning.

I am also impressed by the fluency and comprehension of many for whom English is not their first language. I briefly touched on some of the difficulties experienced even by users of English as a first language in a previous post about spelling. Sometimes I wonder that communication is possible at all, especially when considering local idioms and sayings that make little sense out of context, but largely go unnoticed. What must a new speaker of English think when encountering “Bite the bullet, break the ice, butter someone up, or even bring a plate”.

How difficult it must be too, when words, like vice for example, have multiple meanings.

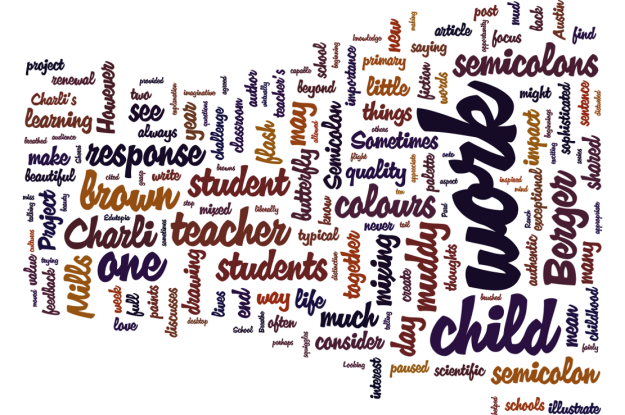

This week at the Carrot Ranch Charli Mills has been talking about vice. Her article is about the not-so-pleasant type of vices. As usual, I like to be the contrarian and consider alternative viewpoints. That might be considered one of my vices. Sometimes I laugh when a thought takes me to a context far away from a speaker’s intended message. Other times I fail to see the intended humour, reading beneath the surface intent to hidden messages.

To illustrate this I will use two recent examples:

The cyclist and the flight attendant

He: a cyclist, just entering the last third of his life (about 60, give or take 5 years)

As his bike was being loaded onto the plane he explained that he had ridden from Alice Springs to Uluru, the long way. (I’m not sure of the distance of the long way, but the direct way would be more than long enough for me!)

She: a flight attendant still in the first third of her life (about 25, give or take 5 years)

“That’s so awesome! I hope I continue to exercise all my life.”

I didn’t hear his response; I was laughing too hard: the innocence and blindness of youth. How well I remember thinking anyone over about thirty was at death’s door. What amuses me now is the number of people my age who think we are much younger than those of the previous generation at the same age. I think the blindness and selective sight continues throughout life.

Of course I interpreted her words to mean: “You’re so old. I can’t believe you could do that. I hope I can still exercise when I am as old as you!”

The joy of fatherhood?

Waiting for the same flight was a father and his daughter, approximately two and a half years of age. The daughter was doing what any child of that age would do: looking around, exploring a short distance away from dad before returning to his side. From what I could see she was doing no harm and was perfectly safe. It was a small airport, she could not wander far.

Each time she moved away he barked a short command at her. Although his words were not familiar to me, I had no difficulty interpreting them. As with most children, sometimes she heeded them, sometimes she didn’t. Sometimes he repeated the command, or retrieved the child. Sometimes he didn’t.

Then I saw his t-shirt and read the word emblazoned on the front. I am a reader. Sometimes I wish I were not. The words read, “Guns don’t kill people, Dads of daughters do”.

I have never “got” the need for messages on apparel, and definitely not a message as negative as this. I assume it was meant to be amusing, but I could see no humour in it. Maybe he didn’t understand the message underlying the words (he was speaking in a language other than English). Maybe I read too much into it. Apparently though, according to this Google search, there is a sizable market for shirts and products extolling these sentiments, some even with the inclusion of the word “pretty”.

My interpretation of the subliminal message is one of acceptance of a number of vices, and my belief is that until we can obliterate the insidiousness of messages such as these from the common psyche, our society won’t much improve. To me the message commends: disrespect for others, sexism, murder, violence, antagonistic relationships between parent and child/father and daughter, an absence of nurturing, an acceptance that children are difficult and a burden . . .

Perhaps I should stop there. I think this father and daughter team would be prime candidates for the early learning caravan project I wrote about recently. I would love to help this father see, not only the power in his words, but the treasure his daughter is and the importance of their relationship.

As I’ve explained, I sometimes see humour in words where it’s not intended, and fail to see it where it is. I’ve attempted to include humour in my flash response to Charli’s challenge to In 99 words (no more, no less) write a story that includes a vice, by using three different meanings of the word. I’ll be interested to know if my “humour” matches yours, but won’t be surprised if it doesn’t!

This one is definitely not about Marnie!

Vice-captain

She almost danced along the verandah. What would it be: medal, certificate, special recommendation?

The door was open but she knocked anyway.

“Come in.” The command was cold. A finger jabbed towards a spot centre-floor.

Confused, her eyes sought the kindness of the steel blue pair, but found a vice-like stare.

She obeyed.

“In one week you have led the team on a rampage:

Smashing windows

Uprooting vegetables

Leaving taps running

Graffiting the lunch area . . .

We thought you were responsible. What do you have to say for yourself?”

“But sir,” she stammered, “You made me vice-captain!”

Thank you for reading. I appreciate your feedback. Please share your thoughts about any aspect of this post or flash fiction.