Teaching critical literacy through picture books

This is the fourth is a series of posts about the role of picture books, especially The Very Hungry Caterpillar by Eric Carle.

The purpose of this post is to discuss the importance of critical literacy and the necessity to teach children to

- think critically

- not accept everything that is presented in text (oral, visual or print)

- evaluate the source of the information and the intent of the author

- match incoming information with prior knowledge, and

- question, question, question.

In these previous posts

Searching for meaning in a picture book – Part A

Searching for purpose in a picture book – Part B

Searching for truth in a picture book – Part C

I suggested ways of including The Very Hungry Caterpillar in an early childhood classroom and discussed the responsibility that authors have in differentiating between fact and fiction in story books.

In Searching for truth in a picture book – Part C I pointed out the inaccuracies in The Very Hungry Caterpillar and the pervasiveness of the misconceptions, if not totally attributable to the book, then at least in part. This is verified by Jacqui who, in 2011, wrote on the Monarch Butterfly New Zealand Trust website

“When speaking to teachers I often find raised eyebrows when I explain that butterflies’ larvae do not make cocoons. The teachers refer to Eric Carle’s book, The Very Hungry Caterpillar, where he refers to a ‘cocoon’.”

Note that Jacqui refers specifically to this book, rather than to sources in general.

As shown by Jacqui, though, it can be difficult, even for teachers without specialist entomological knowledge, to sort out fact from the fiction.

These are two pieces of misinformation contained in the story:

Misinformation 1:

Caterpillars eat a lot of different food

Fact

Most caterpillars are fussy about their diet, some eating only one specific plant, others eating a variety of plant foods.

Misinformation 2:

Butterflies come out of a cocoon.

Fact

Butterflies emerge from a chrysalis.

Moths come out of a cocoon.

Watch these two videos:

This one by Strang Entertainment shows the caterpillar becoming a chrysalis.

This one shows a silkworm caterpillar spinning a cocoon (about 2 mins in).

They are two very different processes.

However a quick glance at these Google search results shows just how pervasive the misconceptions are:

Even seemingly authoritative educational websites misinform. Look at the way these two websites promote themselves, and consider the misinformation they are peddling.

The website Math & Reading Help

states that The Very Hungry Caterpillar is “factually accurate . . . teaches your child to understand this biological process … a butterfly. . .(is) a caterpillar that has emerged from its cocoon”

Primary upd8 which promotes itself as “UKs most exciting science resource”

also suggests using The Very Hungry Caterpillar for teaching about the life cycle of a butterfly.

If self-professed “authorities” can’t get it right, how are we laypeople meant to make sense of it. Suggestions like these reinforce the need for the skills of critical analysis to be developed.

Unlike those above, I contend that this book has no place in the science curriculum. Its greatest value is as a tool for teaching critical literacy.

When children have learned about the life stages of a butterfly and then listen to The Very Hungry Caterpillar, they are very quick to pounce on the inaccuracies and immediately want to write to the author and tell him of his mistake.

When told that he already knows and that he isn’t going to change it, as confirmed in an interview reported on the Scholastic website, they are incredulous.

“Why would he do that?” they ask.

Why indeed.

When told that he doesn’t care that it isn’t right, they are indignant.

But herein lies its value:

I am able to affirm their learning: they know more than Eric Carle; and, more importantly, I am able to reinforce with them that just because something is in print, doesn’t make it true.

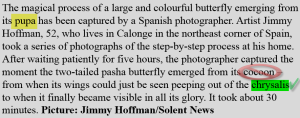

In addition, it is important for them to realise that misinformation does not occur only in picture books, nor only in this picture book. It is just as common in news media, as shown by this article from Brisbane’s Courier-Mail on December 7 2013

Nor is misinformation restricted to caterpillars and butterflies.

This article, again from the Courier-Mail, on January 26 2014 also contains inaccuracies:

Squirrel gliders don’t fly, and they don’t have wings.

Suggestions for teachers and parents:

- point out inaccuracies and inconsistencies

- encourage children to think about what they are reading and hearing and to evaluate it against what they know

- support children to verify the source of the information and to check it against other more authoritative/reliable sources

- help them to recognise that every author has a purpose and to identify that purpose

- invite children to ask questions about what they are reading and to interrogate the content

- encourage them to question, question, question.

As demonstrated by the Google results shown above, there is a good deal of misinformation available, often cleverly disguised as fact. Being able to navigate one’s way through it is a very important skill.

Eric Carle says “If we can accept giants tied down by dwarfs, genies in bottles, and knights who attack windmills, why can’t a caterpillar (sic) come out of a cocoon?”

What do you think?

Do picture book authors have a responsibility for informing their audience? Is a butterfly coming out of a cocoon in the same realm as giants tied down by dwarfs? Would we accept a child hatching out of an egg? What parts of a story should be based in reality and which parts can be imagined?

“Why can’t a butterfly come out of a cocoon?” asks Eric.

Well, Eric, they just don’t.

Please share your thoughts.

Pingback: Which came first – the chicken or the duckling? | Norah Colvin

“Unlike those above, I contend that this book has no place in the science curriculum. Its greatest value is as a tool for teaching critical literacy.” Norah, this statement sums it all up. I don’t think Eric Carle writes necessarily for scientific accuracy. His goal is to create books that children love and parents and teachers will buy. For the very young it doesn’t matter, but for school aged children, I think parents and teachers both need to help children learn to read critically and check the accuracy of the source. Sadly, many adults don’t do this themselves as can be seen by some of the inane remarks people make in social media.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your comment, Michelle. It is true. Eric Carle’s intention was not to write a scientific text. It was to write a colourful, fun and engaging picture picture that children and adults would love to read and share. He did that very well. It is not his fault that others think to use it as a text for teaching science. Perhaps those teaching science from a picture book should learn to choose more reliable sources! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m finding your picture book theme really interesting, Norah – really makes me think. I like your idea of using the misinformation in The Hungry Caterpillar to empower children, showing them they can be cleverer than adults. Obviously, your focus is education, but I wouldn’t want to lose the idea – and I’m pretty sure you wouldn’t either – of reading for entertainment. I was going to say that then it might not matter if the facts were wrong, but actually it would: it detracts from our ability to involve ourselves in the story if there is a mismatch between what we know within the story and outside it. It’s similar to what I’m exploring in my blog series of fictional psychologists: if the writer has them doing things even a pretty duff psychologist wouldn’t do (like reading casenotes in a cafe) the story is lost for me.

I wish you’d do a post on Father Christmas. Like Bec, I really don’t like him – I think because adults provide too much evidence to suggest he is real. This smacks of being about the needs of the adults rather than the child, but it depends upon the particular context, I guess, and how much fantasy is enabled within the relationship already.

LikeLike

Hi Anne,

Thank you for sharing your wisdom in your comment. I certainly wouldn’t want to diminish the pleasure of reading fiction. I spent some time in the previous posts expounding the benefits of reading to children and many things I love about “The Very Hungry Caterpillar”. However, having taught children about the life stages of a butterfly, and knowing that what is described in this book, though not scientifically correct, is often recommended as a resource makes me cringe a little. I don’t know why I feel so strongly about this one. Maybe because the misinformation is so pervasive. Maybe more because the author didn’t care about the misinformation. I’m not sure. There are plenty of stories about children being delivered by a stork or being found under a cabbage leaf and I don’t mind that so much. I don’t think that misinformation has such a sturdy existence.

Like Bec, you mentioned Santa. Then there is the Easter Bunny, the Tooth Fairy… I’m not really sure I want to tackle these. Maybe you or Bec could start off the discussion. I know Bec feels quite strongly about the Santa ‘lies” she was told as a child. I don’t feel so strongly about the stories I was told as a child, or told as a parent. I quite like itsmagic and warm fuzzies. But I am happy to discuss it. As you say, maybe my maintenance of the story was to regain (my need) some of the magic and wonder of my childhood. I could probably over-dramatize here and say there was little else, but maybe I shouldn’t go that far!

Thank you for your contribution. May the conversations continue!

LikeLike

May the conversation continue indeed, and great place for it to happen..

What I wonder about what you’ve said about this book is not so much the initial mistake about caterpillars and cocoons but the apparent refusal to acknowledge it. Even if it were too complicated to substitute the correct term in later editions, why insist that it doesn’t matter whether or not children pick up the truth? It makes me think about what you’ve written here about how being challenged in our views can facilitate learning but sometimes we find that challenge really tough and can go through all kinds of intellectual contortions to avoid it.

LikeLike

Thanks for sharing your further thoughts on the topic, Anne. I like the way you suggest that sometimes we use intellectual contortions to maintain opinions and beliefs under challenge. I can think of many “big” topics that may fall into this category e.g. creationism and climate change. On a more personal level there are many other issues that may fall under the same spell e.g. justifying one’s own or excusing another’s behaviour, persisting with a belief (e.g. in Santa, now that that topic has been raised, to receive gifts) long after the evidence suggests otherwise. As you say, sometimes the challenge can lead to learning if one is open to it. At other times the challenge or conflict may be avoided or ignored e.g. not listening to the differing opinions of others, and so no learning ensues. Personally, if I was to make an error in a publication, which is quite possible, I would like to have it pointed out so that I could right it. I prefer to think that I wouldn’t stubbornly persist with a falsehood and then use intellectual contortions to justify it.

LikeLike

Hi again Nor and Anne! I think, Nor, it sounds like you are describing ‘motivated reasoning’. I love this (though actually loathe it – a terribly destructive Thing We Do – I guess I love thinking about it!). I have possibly mentioned before the cognition study where numeracy and “intellect” were accounted for, and – long story short – people interpreted the same set of data in significantly different ways based on whether the context given for the data supported or challenged their ideologies. In fact, yesterday I went to a seminar on the role of identity processes on the environmental predilections (or not) of the public, and it was very interesting. Again, demonstrating how we can become even MORE STRONGLY opposed to something when we are presented with evidence that challenges our values structures – something I suppose we all know from life experience.

Here’s a link to a write up on the cognition article: http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/how-risky-is-it-really/201309/the-smarter-we-are-the-dumber-we-get-about-facts

LikeLike

Hi Bec,

Thank you for another of your very insightful and challenging comments. I have just read the article you mentioned and it certainly provides much to think about. I know that I have sometimes caught myself out defending an institution which I would not normally defend but which, in the context, seems no less worthy than that with which it is compared. When finding myself doing this I have often wondered why. At times I have thought it to be a little like defending a family member from outside criticism, even when agreeing (in private) with the criticism. I like the way your comments and Anne’s comments both challenge and extend my thinking and learning. You are both leading into far deeper waters than I intended when writing these posts.I would love to hear more about the information shared in the seminar you attended.

LikeLike

Interesting reference, which I had to read couple of times to understand, maybe partly because of being sort-of numerate and lazy, didn’t want to accept the implication that I use my brain to support the arguments I favour. But of course!

LikeLike

Hi Anne, I feel a bit like I’m ‘butting into’ your comment exchange! But I read what you wrote about Santa, and I would really like to hear more. Norah says she doesn’t feel ready to tackle that topic, but I recall reading your guest post, and some other things you have written and you have a great way of exploring complicated topics. Maybe at some point you could consider writing about the myths adults teach to children?! In any case, it would be great to know more of your thoughts. Best wishes 🙂

LikeLike

Thanks for butting in, Bec. I think it’s great when the conversation branches out on these blogs.

Like Norah, I’m not sure I want to write about Santa just now, but would happily join in if you found a way to write about it on your food blog! But I appreciate your encouragement and will certainly bear it in mind.

I do have a Santa-disappointment scene in one of my as-yet-unpublished novels and you’ve got me thinking a bit more about why it’s there. It’s something about a character who has difficulty separating fantasy from reality in later life, although wouldn’t want to generalise from this – most of us, as Norah says, manage this quite well despite a lot of blurring.

Also going to check out your blog to see if you’ve answered your Liebster questions yet.

LikeLike

Hi Anne (and Nor!), thanks for writing back, and I love the sound of your up-coming novel. I hope your writing is going productively! Not sure I can see the segue from food to Santa, but if the opportunity arises I’ll grab the soapbox and give it a go! Perhaps Christmas pudding gives a nice link 🙂

LikeLike

Thanks Nor, very thought-provoking. It’s great that you can see the value in demonstrating to children that not everything in print – not everything coming from an adult! – is truth. Santa Claus is another good example. Although I personally don’t like the idea of perpetuating the myth of Santa Claus to children, at least those children will grow up and hopefully question other things they were told to believe by adults, which actually were lies.

It’s only a tangential link, but I had a discussion with a friend about ‘fairies’. She likes the idea of children thinking fairies are real, and having genuine hope that they will see one when they play in the back of the garden. But I disagree, I think it’s cruel to encourage children to hope for something that will never happen. Instead, I think we could use imagination and creativity to make the most of the amazing things that do exist. Fireflies, for example, are so exciting and amazing, and DO exist! So I suggested to my friend that rather than fairies, children could be encouraged to hope to see a firefly, and maybe learn about the lifecycle, and plant host species of plants in the garden in the hopes that they will be seen. I don’t see why mythology is needed to tell an amazing story – the world is an amazing place as it is. (Though that doesn’t mean I don’t like mythology and fantasy – just that there is room for more, e.g. a scientifically accurate fictional story about a caterpillar!)

LikeLike

Hi Bec, Thanks for your comment. It also includes much to ponder. I agree that the world is indeed an amazing place with an incredible variety of things to marvel at and wonder about. Just today I saw on my front fence an amazing flower that looked just like a starfish. I had never seen one before and it certainly brought a little wonder to my day. I was so fortunate to see it as this afternoon it had wilted and curled up. I would not have noticed it.

I’m inclined to agree with your point about fairies. Perhaps stories of fairies were inspired by sightings of fireflies. While I love the idea of fairies, I’m not sure that I ever thought of them as anything other than imaginative, along with dragons and unicorns.

I think the issue of Santa goes way deeper than is possible for me to delve into here. Personally, I love the magic of the story; but I know that you were never keen on the lie.

Is your message, perhaps, that the lines between fantasy/mythology and science should not be blurred? And that children should know that fanciful and imaginative stories are just that and not have them promoted as real?

LikeLike

Hi Nor, thanks for the thoughts, I’m not sure how to respond to your questions as it’s not something I have thought through clearly. I suppose it’s about representation, promotion, and use. If something like the VHC is promoted as an educational resource, then perhaps the onus of responsibility is on those making that claim, not the author. But then if the author has written a book with the intention of using a scientific concept as the basis for appeal, then perhaps there is responsibility there with the author, too.

I really enjoy science fiction books and films, and often there will be adaptations of “real” science in the fiction, which adds an element of realism and I suppose a point of familiarity. But I don’t see the same trouble.

Similarly, I learned a lot from ‘Shogun’ by James Clavell about historical Japanese society, but I would be naive to accept the intricacies of the story as historical fact. Rather, it’s the overall message, tone, and content that offered insights. Maybe with the VHC, the author is providing a comparably accurate ‘big picture’ of the butterfly life cycle, but is skewing some of the ‘pixels’ (to borrow from terminology used by Julia Gillard in a recent article about schooling in Australia) for the sake of creative licence; just like how James Clavell created inter-character relationships which couldn’t possibly have been elicited from historical documents.

Even though I’m giving that analogy, I still feel that it is different, though not entirely sure how. Maybe because of, as you say, the way we systematically and institutionally undermine the self-determination and empowerment of children so that they are subservient, in which case we have an obligation to provide materials which are not at odds with the box in which we make children exist.

LikeLike

Thank you for your challenging response, Bec. You have raised some very interesting issues.

I agree that the onus for the promotion of the book for use as a resource in teaching science lies with the one making the claim, rather than the author. I guess Eric Carle’s purpose in writing the book was simply to entertain and it certainly does that very well. Its widespread popularity testifies to that, as does the wide range of merchandise available. Just recently I even saw some Very Hungry Caterpillar pushers (strollers, prams). I did acknowledge the worth of the book in previous posts but object to its promotion as a resource for science teaching. Maybe I should be focusing my article on those promoting it rather than the author? That authors may be bestowed with a ‘creative licence’ is interesting in itself.

I am grateful for the comments that this post has encouraged. We all seem to agree on a certain level of discomfort with the misinformation in this book as well as an inability to pinpoint just why. Perhaps the conversations will help us clarify.

LikeLike