What is the purpose of picture books? Is their purpose simply to entertain with an interesting story and rhythmical language that is fun to read and recite? Is it simply, as I said in my previous post Searching for meaning in a picture book – Part A, “. . . a special time of togetherness, of bonding; of sharing stories and ideas . . . “ Could the purposes of picture books extend beyond entertainment alone? I think most people would acknowledge that reading picture books to young children has a profound effect upon children’s learning and development. In addition to entertainment, picture books can be used for a multitude of purposes, including:

- to encourage a love of reading and books

- to develop vocabulary and knowledge of language (through immersion and engagement rather than direct instruction)

- to provide a link between the language of home and the language used in the wider community and in education

- to support children embarking on their own journeys into reading

- to inspire imaginations

- to provide opportunities for discussing feelings, emotions, ideas, responses

- to develop feelings of empathy, identification, recognition, hope

- to instill an appreciation of art by presentation of a wide variety of styles, mediums and techniques

I’m sure you can think of many more than I have listed here. But what of knowledge, information and facts?

How, and when, do children learn to distinguish fiction from fact, or fact from fiction? At the moment that question is too big for me to even think about answering, but it is a question that I ponder frequently and may return to in future posts.

Children seem to realise early on that animals don’t really behave like humans and wear clothing.

They don’t expect their toys to come to life and start talking.

They quickly understand, when it is explained to them, that unicorns and dragons are mythical creatures and, to our knowledge, don’t exist.

But what happens when the lines between fact and fiction blur and content, though presented in fiction, has the appearance of being based in fact? For example: The lion is often referred to as “King of the jungle” and appears in that setting in many stories. However, lions don’t live in jungles. According to Buzzle, they live in a variety of habitats and jungle isn’t one of them. You knew that didn’t you? But what about the children? When will children learn that lions are not really kings of the jungle? Do you think it matters if children grow up thinking that lions live in jungles?

What about when animals that don’t co-exist appear in stories together? For example: Penguins often share a storyline alongside polar bears. Does this encourage children to think that penguins and polar bears co-exist? When do adults explain to children that penguins and polar bears live at opposite ends of the planet? At what age do you think children will happen upon that information? Does it matter?

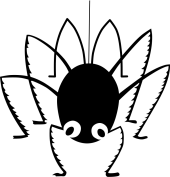

What about the way animals are visually portrayed in stories? Must the illustrations be anatomically correct? For example: We all know that spiders have eight legs. Right? If I was to ask you to draw a picture of a spider, how would you do it? Have a go. It will only take a second or two. I can wait.

Now compare your drawing with these:

How did you go?

While children easily realise that this picture is fictional:

They have less success is understanding what is wrong with the previous images. Spiders have eight legs. Those drawings show eight legged furry creatures. The story says they are spiders. That must be what spiders look like. Right? Unfortunately, real spiders look more like this one:

All eight legs are attached to the cephalothorax, not the abdomen (or even one body part) as shown in most picture books. While I am sure you drew a spider correctly (didn’t you?), most children and many adults draw them more as they are depicted in children’s stories. Is this a problem?

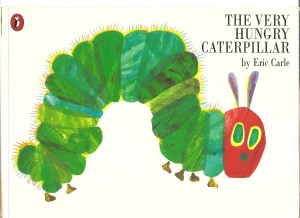

I am not for one moment suggesting that we get rid of fictional picture books and stories. I love them! And as I have said, and will continue to say, many times: they are essential to a child’s learning and development. There is no such thing as too many or too often with picture books. Instead, I would like you to consider the misconceptions that may be developed when the content of picture (and other) books may be misleading, and how we adults should handle that when sharing books with children. One of the books that gets me thinking most about this topic is “The Very Hungry Caterpillar” by Eric Carle.

As I said in a previous post, it has been published in over 50 languages and more than 33 million copies have been sold worldwide. I am almost certain that you will be familiar with it, and upon that assumption, I have one final task for you in this post. Please share your response to the question in this poll:

To be continued . . .

I would love to receive any other comments you would like to share regarding the content in this post.

I do apologize that I have been unable to get the text and pictures in the layout I desire. I obviously have more investigations to carry out and learning to do. 🙂

Maybe next time I’ll have it mastered, says she, hopefully!

Pingback: Which came first – the chicken or the duckling? | Norah Colvin

Whether or not the pictures or the story itself is factual is not the issue. The main thing I looked for in books for my little ones, were comfy, cozy books that would not frighten them, imbue a love of reading, with colorful pictures to keep them turning pages. Do we question the accuracy of the illustrations? My children had no difficulty discerning the picture book spider, penguins, or talking cars from the real thing, even as young toddlers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Michelle. It’s great to hear your thoughts. I agree that turning children onto reading and into readers is what is important. This is a wonderful book. I do not deny that. The ability of toddlers to differentiate real from imagined at such a young age is amazing isn’t it? I forever remain in awe of children’s ability to learn. We humans are pretty amazing creatures! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Searching for truth in a picture book – Part C | Norah Colvin

Nora, thanks for this post. Very interesting. Having been trained as a professional scientist and loving picture books, this really made me think. There probably is no simple answer between “absolute accuracy” and “story-telling.” I suspect, however, that many misconceptions (such as your great example of the spider’s legs) can’t really be blamed on picture book illustrations. Do people ground their factual knowledge on them? It could be that yes, even if in an unconscious way.

LikeLike

Apologies for mis-spelling your name!

LikeLike

That’s fine. I’m used to it. I would say, what’s in a name, or as in this case, the spelling; but that is getting very close to the topic of the next article in this series!

LikeLike

Hi Marialena,

Thank you for your double comment. I experience that difficulty myself sometimes when posting comments. I appreciate your persistence. You have a little more content in this one than the previous. I like your term “absolute accuracy” and even wonder about it. There is so much we are yet to know. I get the impression that you, as a professional scientist, are not too concerned about that accuracy in picture books and the effect, if any, it may have upon the development of misconceptions. I guess it is in the realm of science, not fiction, where the responsibility for teaching and learning scientific information lies?

LikeLike

Nora, this is very interesting. As a person trained as a professional scientist who loves picture books, you really made me think. I don’t think there’s an easy answer. I do suspect, however, that many misconceptions (like the spider’s legs from the cephalothorax) can’t really be laid at the feet of picture books themselves. Thanks for the challenge!

LikeLike

Hi Marialena,

Thank you for visiting and your comment. It is interesting to receive the thoughts of a professional scientist. I agree that the misconceptions cannot be laid, wholly, at the feet of picture books. However, I do wonder how much the content of picture books contributes to the making of misconceptions. I will be talking about this some more in a future post. I hope you will stop by again and tell me what you think of that. I, too, enjoy a challenge!

LikeLike

Hi Nor, Thanks for the article, it’s really interesting to think about the role and impact of false information. I wonder if there is a positive upshot that children who do learn as they get older that some ‘facts’ were false, become more critical of other information sources? I don’t know, but it is a topic I am looking forward to learning more about – from you!

LikeLike

Hi Bec,

Thanks for your comment. I think it’s important to be able to separate fact from fiction, but it’s not always easy to do so, particularly when the fiction has been part of the common ‘lore’. Sometimes it is difficult to recognize, particularly when we are expected to accept, rather than question.

You will hear more from me on this topic!

LikeLike